MALI, THE DOGONS AND TIMBUKTU

Almost three years ago, when

Marianna Pencharz

asked me to

join her on a trip to Timbuktu,

my response was: “Yes, of course,” pause: “Where exactly is it?” We

have just

returned from that long-planned trip to Mali

and we have a photo by a sign that says “Welcome to Timbuktu.”

See This Week's

Picture

Almost three years ago, when

Marianna Pencharz

asked me to

join her on a trip to Timbuktu,

my response was: “Yes, of course,” pause: “Where exactly is it?” We

have just

returned from that long-planned trip to Mali

and we have a photo by a sign that says “Welcome to Timbuktu.”

See This Week's

Picture

Towards the end of the trip I was overwhelmed by

the

poverty, the dust, the black plastic bags that lay scattered all over

small

hamlets, by visiting a long list of dusty markets and villages, being

the butt of the ever persistent

vendors,

and kids asking for cadeaux. But

distance

gives perspective and I look back and appreciate the interesting places

we

visited. It was a most enjoyable three weeks.

There are over 16 million people living in Mali.

Most live

on a subsistence level, based on agriculture, fishing or herding, cows

or goats.

The

French were there for almost 100 years until independence and their

presence is

still felt in the common usage of French as the lingua franca and the

surprisingly delicious baguettes and flutes. The distances between

places are far

and dusty over dirt tracks or piste. Our group of 9 traveled by

minivan, jeep,

and desert truck as well as 3 glorious days sailing on a pinasse on the

Niger River.

Our party gathered at Bamako

where we were introduced. Ian, Janet and Jim relax after

at the

briefing.

Our party gathered at Bamako

where we were introduced. Ian, Janet and Jim relax after

at the

briefing.

Making our way north we stopped at a Bambara village to

see how

they make Shea butter or karite. The nuts ripen at the same

time as millet

and sorghum – the main grains of Mali. The women dig a hole

and

place the nuts inside. In late January during the dry season,

when there

is not so much to do, the women take out the nuts and roast them, crack

the

shells and then pound, cook and purify the meat inside. The resulting

shea

butter is formed into large slabs. The family sets aside what they need

for

cooking and other household uses and then sells the rest at markets in

spiked

balls of shea butter. It is the main oil

for cooking and especially useful as it doesn’t need refrigeration.

Baobab trees dot the landscape. The trunks are

stripped of the bark to make ropes. The branches

support woven

bee hives. Mali

honey is dark and delicious, almost like maple syrup

A calabash field. The

calabashes will be sold as

containers

and as units of measure – most places sell dry goods by volume.

We overnighted at Djenne to see the famous Monday

market and

mud mosques. The ancient mosque with 100 pillars and numerous towers is

made

from special deep mud by master masons. The wooden poles are for

decoration but

also act as scaffolding when the mud plaster is renewed annually by the

people.

This is a UNESCO World Heritage site and many buildings have been

restored by

the organization.

Monday

market

Marlene

with our favorite vendor

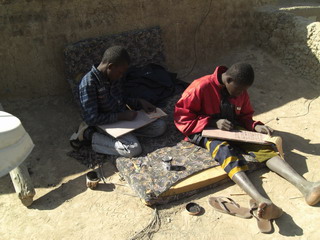

We saw French schools and madrasas where secular

studies like math, geography, French etc

are

taught. Poor parents from outlying areas send their children to towns

to study the Koran. The students prepare

a wooden board covered with fine mud

and then copy a sura from the Koran onto it. After learning it by rote

(and not

understanding the meaning, we were told) they are tested. Afterwards

they re-cover

the board and then copy out the next passage. Only as adults will they

learn the meaning of what they studied.

This picture taken in Timbuktu is of

Talibe, young children who

literally live and learn on the streets. They have no formal education,

unlike

the children who learn in Madrasas. They walk

around

with little buckets that the local population (and us tourists) are

expected to

fill with

food for them and their teacher.

<>

Our next main stop was on the Bandiagara

escarpment. We

stayed at the delightful La Falaise, with its attractive courtyard

and great gingembre

or ginger beer. We ate a lot of couscous and rice during our trip

as well as stringy chicken and delicious kapitaine or Nile Perch. We

also tasted mutton in peanut sauce and yam. The food was generally

good but surprisingl;y expensive, like everything else in Mali.

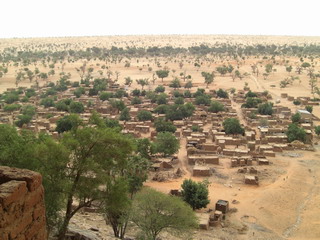

The escarpment, better known as pays Dogon, is

home to

many animists. Although 90% of the population claims to be Moslem,

animism has

strong roots in these outlying villages. The village houses, like most

of the

rest of Mali

are made from mud. We visited Songho village. Families live in

compounds with a

sleeping area, a room for each wife and a toilet. In addition there are

a

number of thatched granaries, either to store millet or female

granaries which

act as a treasure kist for the wives. A powerful and rich leader

decorates his granary with animal skins, a Dogon ladder and millet

sticks. What appears to be a window is actually the only entrance

to the granary.

On the ridge above the village there is a

circumcision

ceremony every three years for boys aged 10-13. They remain secluded

for a

month and learn adult secrets. They then have a race. The winner is

given a

granary of millet, the 2nd is promised the most beautiful

girl, and

the 3rd gets cattle and goats.

Ancient Teli houses above the newer

Dogon houses.

Today the village is in the valley below but the ancient buildings are

still used

for storage, burial and ritual.

Modern Songho village

Modern Songho village

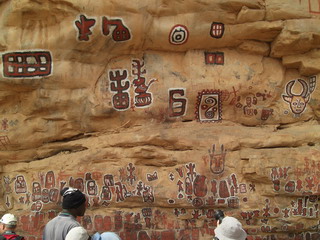

During

the month of healing the boys are instructed in how to be a man and how

to behave. Circumcised boys don’t draw new paintings but repaint

ancient ones. Our local guide told us that young girls are also

circumcised.

During

the month of healing the boys are instructed in how to be a man and how

to behave. Circumcised boys don’t draw new paintings but repaint

ancient ones. Our local guide told us that young girls are also

circumcised.

We also visited Neogora a very

secluded hillside

village.

The steps are the only way into the village. Everything has to brought

up into the village via these steps.

We also visited Neogora a very

secluded hillside

village.

The steps are the only way into the village. Everything has to brought

up into the village via these steps.

The roofs are used for drying

hibiscus leaves for

tea,

peppers and calabashes

The roofs are used for drying

hibiscus leaves for

tea,

peppers and calabashes

The tour was quite tiring. Here most of our group

gets a

welcome afternoon nap before the masked dancing at Emde. The masked

dances were extremely powerful; they describe the world and have a

strong ritual element. Even today

children

are not allowed near the dancers lest they identify the dancers.

We met a Dogon priest Rojokuma who practises fox

divination. In the late afternoon people come

and ask

him questions. He places sticks and stones in a certain order and

scatters

peanuts within the squares. At night the jackals come to eat the

peanuts. According to

their foot

prints he is able to divine the future and the correct answer.

Mopti is one of the main ports. We saw salt slabs

from the

salt mines in the north, brought to Timbuktu

by large camel caravans. Each camel carries 2 slabs on either side.

From Timbuktu the salt is taken by boat along the river.

Everywhere we saw and smelled smoked and dried

fish. The main

fish is

tilapia, but also little catfish. The fish were so small; I fear it

points to overfishing. The Bozo people are nomadic fisherman. In the

dry season when the rivers shrink, they follow the fish and live in

temporary huts along the banks of the Niger river.

We also saw many onion fields,

part of a US Aid project. Mali

exports

onions, both fresh and dried. Onions formed the basis of many delicious

sauces. Along the river banks we saw people watering the onions by pump

but also by calabash. All villages have wells and it is hard work

drawing water. Some villages did have hand pumps. In the towns well

water is free but there is a charge for drinking water from special

pumps.

At the boat yard in

Mopti we saw how the men shape

mahogany planks

to make their boats and also how they make nails from the bodies of old

cars. Note bicycle wheel bellows.

er.

We

made our way to Timbuktu

via pinasse. It was wonderful to see life on and along the Niger River

at eye level. The River has its own rhythm and our captain kept a sharp

eye out for shallow banks and often poled to gauge the depth.

We

made our way to Timbuktu

via pinasse. It was wonderful to see life on and along the Niger River

at eye level. The River has its own rhythm and our captain kept a sharp

eye out for shallow banks and often poled to gauge the depth.

A

pinasse ferrying people and goods

A

pinasse ferrying people and goods

Camping on the banks of the Niger

River

Hippos near the river bank

Reaching Timbuktu

our group and Ya-ya our guide take a group photograph.

The people on tour were very widely traveled.

Mali

does not top most people’s ‘must do’ list. The group hailed from

England, USA, and Canada. All had lived outside their

own

countries, working in Africa, Australia

and the Arctic but particularly in

Arab

countries. It was a pleasure to share this adventure with such nice

people.

Timbuktu’s

glory is in its mystique and fabulous past. It was a strategic point on

the trans-Sahara caravan route, where salt, gold,

ivory,

and slaves were traded; as well as an important center for Islamic

learning. We

collected as many Timbuktu

stamps on our

passports as we could, including from the police and the post office. Even today Timbuktu is on the edge of the

Sahara desert and 9 hours by dirt road from the nearest major

town. While some rode a camel a few of us walked the dunes to a Tuareg

temporary dwelling to enjoy Tuareg tea. It includes an elaborate

ceremony of pouring tea from cup to cup and tea pot until it is

foaming. Visitors are expected to have 3 cups of tea - one for life,

the second for death and the third for love.

Children learning at a Madrasa

in Timbuktu

Children learning at a Madrasa

in Timbuktu

The sign at the house where Rene Caillie lived in

1828. He was

the first

foreigner to reach Timbuktu

and return alive. He learnt Arabic and Islam, posing as a devout Muslim

<>

After a long and very dusty ride by desert truck

we reached

Segou where we attended the Festival on the Niger.

The music festival had 2 parts, the day

performances which

were free and the evening performances which charged an entrance fee –

a hefty

100 euro for visitors. We especially enjoyed the day activities with

performances

from Mali, Ghana, Burkina

Faso, Portugal,

Germany, and Mexico.

There

were troupes of dancers, all dressed up who came and danced if they

liked the

music. People in the audience would be overcome, get up and dance and

then go

and sit again. Everybody was there - dignitaries, tourists, locals from

all over as well as the ubiquitous vendors who followed us from place

to place. It was great fun.

Segou still boasts

faded French Colonial

buildings. At the

municipality we join the staff in some Malian dancing

Marianna and Nora

admire mud cloth materials drying on the sand as part of the dying

process. The

spinning

is done by women but men weave the cloth in narrow dtrips and then

paint them.

Marianna, me, Marlene, Willi

and Nora wait for our

ginger

beer or hibiscus tea on a porch above the artisans workshop..

Marianna, me, Marlene, Willi

and Nora wait for our

ginger

beer or hibiscus tea on a porch above the artisans workshop..

We returned to Bamako

where

the group split up, going home to England,

Canada, the States

and Willi

continuing to Morocco.

We look forward to Willi's DVD and Jim's photos.

On the last day in Mali I met up with Sheila

Goldberg, a friend from Israel.

We spent the day at the fascinating Maison des Artisans and the

Fetish

market. Sheila enjoys a welcome pineapple drink. We enjoyed a last

kapitaine fish dinner at the Pirate with Marlene and Willi. The next

morning Sheila and I flew to Addis Ababa

where we

overnighted before we returned to Israel.

Although Mali does not offer exciting scenery it

has many fascinating aspects. We saw a very poor African country where

life is hard and daily existence is all consuming. We saw grandiose

schemes that petered out and also attempts at grass roots projects

which would seem to offer a chance for a better future. Although

Moslem, it is a very mild form of Islam and when people found out I was

from Israel I was always

welcomed.

Should anybody require a guide in Mali, I highly recommend our guide,

Yaya Keita. He is fluent in both French and English as well as in local

dialects. He

is well organized and knowledgeable and was always concerned about our

welfare and safety - even when he was suffering from a bout of malaria!

He may be contacted either at +223-(7)

6106009 or via e-mail

bf07ykyaya@yahoo.fr

Go

to the top of this page

Almost three years ago, when

Marianna Pencharz

asked me to

join her on a trip to

Our party gathered at Bamako

where we were introduced. Ian, Janet and Jim relax after

at the

briefing.

Our party gathered at Bamako

where we were introduced. Ian, Janet and Jim relax after

at the

briefing.Modern Songho village

We also visited Neogora a very

secluded hillside

village.

The steps are the only way into the village. Everything has to brought

up into the village via these steps.

The roofs are used for drying

hibiscus leaves for

tea,

peppers and calabashes

Children learning at a Madrasa

in Timbuktu

Marianna, me, Marlene, Willi

and Nora wait for our

ginger

beer or hibiscus tea on a porch above the artisans workshop..